Mary Anning (1799-1847)

|

|

Portrait of Mary Anning by Benjamin John Merifield Donne, 1850. (GSL/POR/1)

The artist Benjamin Donne knew Mary Anning when he was a boy, his school in Lyme Regis was close to Anning's fossil shop. The portrait, which is a copy of the 1842 painting by an unknown artist [possibly William Gray (1818-fl 1883)], was drawn when Donne was 19 years of age, around three years after Anning's death.

|

Mary Anning was born on 21 May 1799 in Lyme Regis. Her parents Richard Anning (c.1766-1810), a cabinet-maker and carpenter, and mother Mary had at least ten children, with only two surviving to adulthood – Mary Anning and her brother Joseph (1796-1849).

Her father Richard was known locally as a fossil collector, selling his finds to tourists who flocked to the seaside resort at the end of the 18th century. However his death in November 1810 left his family with £120 of debts and having to rely on relief given by the Overseers of the Parish Poor.

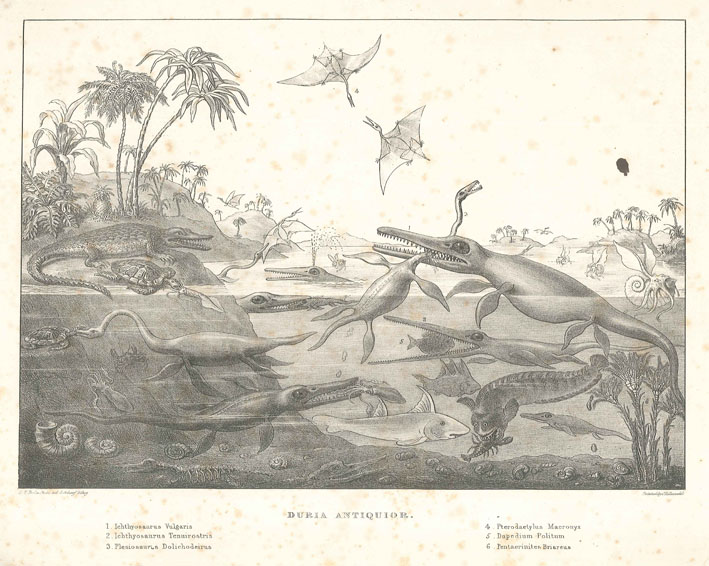

Both Joseph and Mary had been tutored by their father in how to collect fossils. Their first major find, an Ichthyosaur, was discovered by her and her brother in two sections in 1811 and 1812. Other examples of this fossil ‘crocodile’ had been found before, but this was the first to come to the attention of gentlemen scientists in London one of whom, Everard Home, described it in a paper read before the Royal Society in 1814. It was to make her name.

Mary’s second major discovery was of a nine feet long animal, with a small head like a turtle but very long neck. It was described at the Geological Society’s meeting of 20 February 1824 and was recognised by William Daniel Conybeare as being a virtually complete example of a Plesiosaurus. The find not only established the Anning family credentials as fossil dealers, but Mary became a draw in her own right.

Tourists came to Lyme to not only buy fossils but to see her. Lady Harriet Silvester (1753-1843) visited Mary on 17 September 1824 and noted in her diary:

“the extraordinary thing in this young woman is that she has made herself so thoroughly acquainted with the science that the moment she finds any bones she knows to what tribe they belong. She fixes the bones on a frame with cement and then makes drawings and has them engraved...It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favour – that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.”

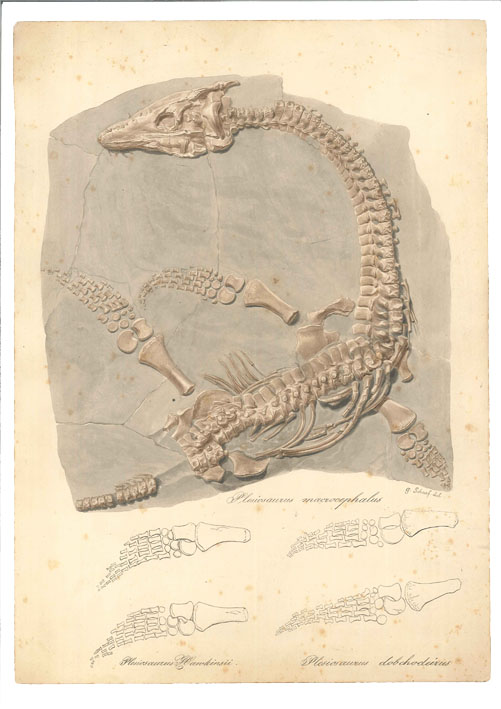

Other discoveries were to follow, such as the ink bags from fossilised squids which could then be ground down to be made in fossil ink. ‘Coprolites’, that is fossil faeces were identified by Mary as early as 1824 and in 1828 saw her third major find, that of a fossil flying reptile [Pterodactylus]. In December 1829 she discovered the fossil fish Squaloraja, seen as the intermediary between sharks and rays and in 1830 her last important find, that of the Plesiosaurus macrocephalus (named by William Buckland in 1836).

By the 1840s, her large fossil finds (and the income they derived) had all but dried up. However, in recognition of her achievements, she received three different annuities and subscriptions raised by the scientific community in the last decade of her life. She died at the age of 47 years of breast cancer.

Link to the expanded 2021 exhibition 'Mary Anning and the Geological Society'.

|

|

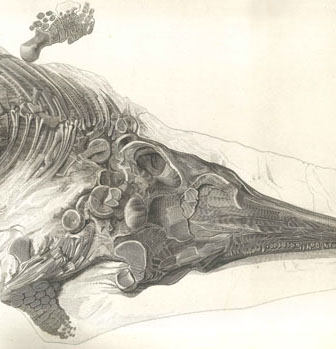

Engraving of a 'Proteo-saurus', 1819 |

|

|

Watercolour painting of a Plesiosaurus macrocephalus, [1838]

|

|

|

'Duria Antiquior', 1830 |

|

|

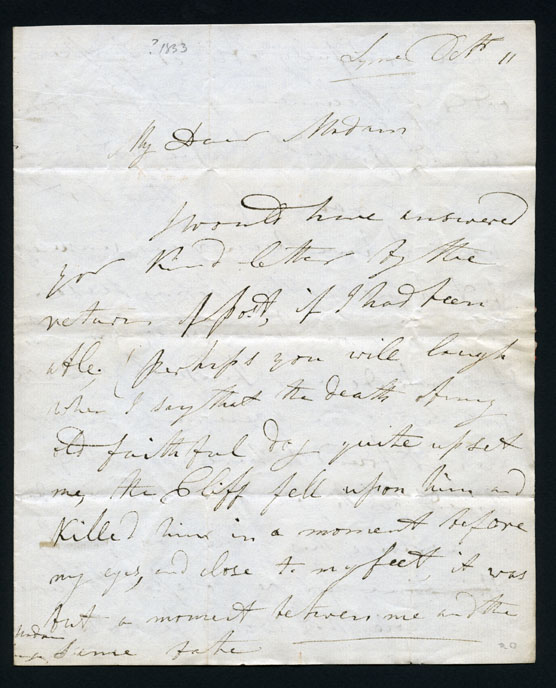

Letter from Mary Anning, [1833] |

|

|

‘Squalo-raja (Spinacorhinus) polyspondila Agassiz’, [1834-1836] |