The Lyell Collection is full of unrivalled content, research, invited review articles discussion papers, thematic collections and much more. Articles are topical, innovative, internationally relevant with global reach. Covering over 100 Earth and planetary sciences.

This month's spotlight is on new, recent and most read palaeontology content.

Published today

Scottish and Irish rocks confirmed as rare record of ‘snowball Earth’

A rock formation spanning Ireland and Scotland may be the world’s most complete record of “snowball Earth”, a crucial moment in planetary history when the globe was covered in ice, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

The study, published in the Journal of the Geological Society, found that the Port Askaig Formation, composed of layers of rock up to 1.1km thick, was likely laid down between 662 to 720 million years ago during the Sturtian glaciation – the first of two global freezes thought to have triggered the development of complex, multicellular life.

One exposed outcrop of the formation, found on Scottish islands called the Garvellachs, is unique as it shows the transition into “snowball Earth” from a previously warm, tropical environment.

Other rocks that formed at a similar time, for instance in North America and Namibia, are missing this transition.

Senior author Professor Graham Shields, of UCL Earth Sciences, said: “These rocks record a time when Earth was covered in ice. All complex, multicellular life, such as animals, arose out of this deep freeze, with the first evidence in the fossil record appearing shortly after the planet thawed.”

First author Elias Rugen, a PhD candidate at UCL Earth Sciences, said: “Our study provides the first conclusive age constraints for these Scottish and Irish rocks, confirming their global significance.

“The layers of rock exposed on the Garvellachs are globally unique. Underneath the rocks laid down during the unimaginable cold of the Sturtian glaciation are 70 metres of older carbonate rocks formed in tropical waters. These layers record a tropical marine environment with flourishing cyanobacterial life that gradually became cooler, marking the end of a billion years or so of a temperate climate on Earth.

“Most areas of the world are missing this remarkable transition because the ancient glaciers scraped and eroded away the rocks underneath, but in Scotland by some miracle the transition can be seen.”

The Sturtian glaciation lasted approximately 60 million years and was one of two big freezes that occurred during the Cryogenian Period (between 635 and 720 million years ago). For billions of years prior to this period, life consisted only of single-celled organisms and algae.

After this period, complex life emerged rapidly, in geologic terms, with most animals today similar in fundamental ways to the types of life forms that evolved more than 500 million years ago.

One theory is that the hostile nature of the extreme cold may have prompted the emergence of altruism, with single-celled organisms learning to co-operate with each other, forming multicellular life.

The advance and retreat of the ice across the planet was thought to have happened relatively quickly, over thousands of years, because of the albedo effect – that is, the more ice there is, the more sunlight is reflected back into space, and vice versa.

Professor Shields explained: “The retreat of the ice would have been catastrophic. Life had been used to tens of millions of years of deep freeze. As soon as the world warmed up, all of life would have had to compete in an arms race to adapt. Whatever survived were the ancestors of all animals.”

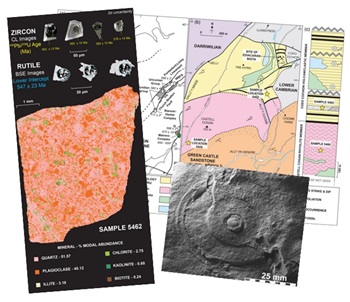

For the new study, the research team collected samples of sandstone from the 1.1km-thick Port Askaig Formation as well as from the older, 70-metre thick Garbh Eileach Formation underneath.

They analysed tiny, extremely durable minerals in the rock called zircons. These can be precisely dated as they contain the radioactive element uranium, which converts (decays) to lead at a steady rate. The zircons together with other geochemical evidence suggest the rocks were deposited between 662 and 720 million years ago.

The researchers said the new age constraints for the rocks may provide the evidence needed for the site to be declared as a marker for the start of the Cryogenian Period.

This marker, known as a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), is sometimes referred to as a golden spike, as a gold spike is driven into the rock to mark the boundary.

GSSPs attract visitors from around the world and in some cases museums have been established at the sites.

A group from the International Commission on Stratigraphy, a part of the International Union of Geological Sciences, visited [July 18-19] the Garvellachs in July to assess the case for a golden spike on the archipelago. Currently, the islands are only accessible by chartering a boat or by sailing or kayaking to them.

The study involved researchers from the UCL, the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, and Birkbeck University of London. The work was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

Glacially influenced provenance and Sturtian affinity revealed by detrital zircon U–Pb ages from sandstones in the Port Askaig Formation, Dalradian Supergroup

By Elias J. Rugen, Guido Pastore, Pieter Vermeesch, Anthony M. Spencer, David Webster, Adam G. G. Smith, Andrew Carter and Graham A. Shields

Read the paper in full in the Lyell Collection by clicking here

Key moment in the evolution of life on Earth captured in fossils

Research published in the Journal of the Geological Society has for the first time precisely dated some of the oldest fossils of complex multicellular life in the world, helping to track a pivotal moment in the history of Earth when the seas began teeming with new lifeforms - after four billion years of containing only single-celled microbes.

The full research paper, ‘U–Pb zircon-rutile dating of the Llangynog Inlier, Wales: constraints on an Ediacaran shallow 1 marine fossil assemblage from East Avalonia’ was published in the Journal of the Geological Society and can be found online here.

The Lagerstätten Collection

Fossil Konservat-Lagerstätten are sites of exceptional fossil preservation that serve as our key archives of evolutionary history, providing snapshots of evolutionary history in a fossil record that is otherwise dominated by cysts, spores, bones and shells. Many, like the Cambrian Chengjiang and Burgess Shale biotas, have received the coffee table book treatment, but for the majority it can be difficult to find a definitive summary. The Fossil Lagerstätten Review Focus series aims to provide distilled contemporary reviews of these evolutionary archives, covering their geological, environmental, ecological and geographic context, as well as providing insights into their preservation, age and evolutionary significance. Collection introduction by Philip Donoghue, Professor of Palaeobiology, School of Earth Sciences University of Bristol, UK.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution of dinosaur tracks in the UK

Dinosaur tracks are a key means of determining the palaeoecology and distribution of dinosaurs through time. They provide an information source that is highly complementary to the body (skeletal) fossil record, but differ in preserving direct evidence of the animals’ interactions with their environment. The UK has a rich history of c. 200 years of dinosaur track discovery, but no recent synthesis exists. Here, we present a new dataset of dinosaur tracks in the UK. This dataset shows a close correlation between the distribution of terrestrial sediments and the preservation of dinosaur tracks through the Mesozoic, providing discrete snapshots into dinosaur communities in the Late Triassic, Mid-Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. The dinosaur track record shows similar broad patterns of diversity and relative abundance of the major dinosaur groups (Theropoda, Sauropodomorpha, Ornithopoda and Thyreophora) through time to the body fossil record, although it differs in that body fossils are also found (albeit infrequently) in marine sediments. There is a broad trend towards higher numbers of track occurrences through time and a notable increase in the relative abundance of ornithopod tracks following the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary. The track record remains an underutilized resource with the potential to provide a much fuller view of Mesozoic dinosaur ecosystems.

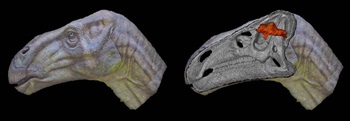

Remarkable preservation of brain tissues in an Early Cretaceous iguanodontian dinosaur

It has become accepted in recent years that the fossil record can preserve labile tissues. We report here the highly detailed mineralization of soft tissues associated with a naturally occurring brain endocast of an iguanodontian dinosaur found in c. 133 Ma fluvial sediments of the Wealden at Bexhill, Sussex, UK. Moulding of the braincase wall and the mineral replacement of the adjacent brain tissues by phosphates and carbonates allowed the direct examination of petrified brain tissues. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging and computed tomography (CT) scanning revealed preservation of the tough membranes (meninges) that enveloped and supported the brain proper. Collagen strands of the meningeal layers were preserved in collophane. The blood vessels, also preserved in collophane, were either lined by, or infilled with, microcrystalline siderite. The meninges were preserved in the hindbrain region and exhibit structural similarities with those of living archosaurs. Greater definition of the forebrain (cerebrum) than the hindbrain (cerebellar and medullary regions) is consistent with the anatomical and implied behavioural complexity previously described in iguanodontian-grade ornithopods. However, we caution that the observed proximity of probable cortical layers to the braincase walls probably resulted from the settling of brain tissues against the roof of the braincase after inversion of the skull during decay and burial.

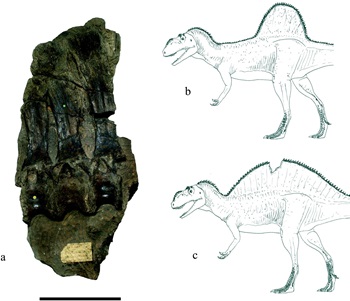

Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: basal Dinosauria and Saurischia

Beginning with Buckland's 1824 description of Megalosaurus, the Geological Society of London played a leading role during the 19th century discovery of dinosaurs in Britain. Here we review the society's role and assess the current knowledge of saurischian dinosaurs in the country. Of Britain's 108 dinosaur species (excluding nomina nuda and objective synonyms), 32% have been named in the pages of Society publications. Britain has a rich and diverse dinosaur record ranging from the Rhaetian to the Cenomanian, and includes a surprising taxonomic diversity. Alleged Lower and Middle Triassic dinosaurs from Britain are suspect or erroneous. Sauropodomorphs represent all of the major clades and several have their earliest global appearances in the British record (Diplodocoidea, Rebbachisauridae and Titanosauria), implying that this region was biogeographically important for this group. The British theropod record is diverse, and includes the earliest spinosaurids, carcharodontosaurids and coelurosaurs. Although some specimens are represented by near-complete skeletons, much material is fragmentary and indeterminate, and c. 54% of British dinosaur taxa are considered nomina dubia. In part this high number results from the genesis of dinosaur science in Britain and the corresponding obsolescence of supposedly diagnostic characters.

Yorkshire’s first embryo-bearing ichthyosaur was pregnant with octuplets

The remains of between six and eight ichthyosaur embryos, still situated within a fragment of the rib-cage of the parent animal, are described. Each is represented by a string of vertebral centra, some with associated ribs. Other skeletal elements, including possible skull material, are represented only by isolated bones, none identifiable with certainty. The small limestone boulder in which the ichthyosaur specimens are preserved was collected from the beach at Sandsend, near Whitby, North Yorkshire, and derives from the Whitby Mudstone Formation (Hildoceras bifrons Ammonite Biozone) of the Toarcian Stage of the Lower Jurassic. The specimen cannot be identified beyond Ichthyosauria indet. However, it represents the geologically-youngest occurrence of ichthyosaur embryos thus far recorded from the UK and the first such occurrence to be reported from Yorkshire.

Mazon Creek fossils brought to you by coal, concretions and collectors

The late Carboniferous (Middle Pennsylvanian, ∼307 Ma ago) Mazon Creek Lagerstätte found in northern Illinois, USA, is unique for its exceptional biotic diversity as well as the human endeavours, both professional and avocational, that brought vast numbers of fossils and new species to science. In 1997, the Mazon Creek Fossil Beds, exposed along the Mazon River near Benson Road, Morris, IL, became a National Historic Landmark.

Indigenous knowledge of palaeontology in Africa

Compared to other continents, the study of indigenous (non-western) knowledge of palaeontology in Africa is a relatively new field. The literature reviewed here nevertheless suggests a long-lasting string of traditions, geomyths and folklore related to fossilized items on the whole continent and encompassing many African cultures. It is often difficult to estimate the antiquity of these traditions, but the evidence gathered here suggests that they range from the 1800s to pre-colonial times, and up to many millennia. Palaeontological items were collected and used for a variety of reasons, but the African record seems unusual for its scarce use of fossils for traditional medicine. Also, despite substantial efforts, some famous localities with conspicuous fossils still remain without any documented indigenous knowledge. We stress that documenting fossil-related folklore and geomyths is not only a matter of preserving this knowledge or promoting diversity, but is also crucial for establishing strong bonds with local stakeholders to encourage preservation of geoheritage and discover new sites.

Quick links to the Lyell Collection and more

The Lyell Collection home

Thematic Collections

What is included in the Lyell Collection

Rocks and fossils resources can be found here