Academics are increasingly facing threats to their freedom from both governments and the law, says Ted Nield.

Geoscientist 20.05 May 2010

There was a time when a career in public service was considered noble and praiseworthy. But recent scandals embroiling our highest public servants, who blatantly debased the high office into which they were elected, has brought public esteem to a new nadir.

Universities are not public bodies, nor their staff public servants; but they once also basked in this same worthy glow, while their institutions’ independent status helped ensure their freedom. If you don’t cost much, people leave you alone. However, universities are now a huge industry, high up the political agenda, and facing calls for “accountability” that can easily be at odds with the need to preserve intellectual freedom.

During the passage of the 1988 and 1992 Acts that now govern them, universities fended off attempts by the Government to take greater control. The price they paid was having to set up their own internal Quality Assurance Agency (QAA), with the rarefied function of inspecting and reporting on the quality, not of teaching, but of each university’s mechanisms for ensuring teaching quality – a fig-leaf, modestly covering the private parts of institutional autonomy. But the QAA was only established “for fear of finding something worse”. Between it and all the other inspectors who now regularly call, one would be very naive to take up an academic career today, expecting to be left alone to pursue one’s star uninterrupted.

Academics’ second bonus was freedom of expression, which remained protected under law after 1992. Academics are as subject to the laws of libel as anyone else; but at least if convicted they would not lose their jobs, and might, if they lived as long as Old Testament patriarchs, be able to pay off any damages awarded against them. And anyway, when would any academic have recourse to law in an academic dispute?

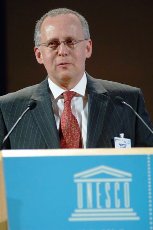

Well, across the Channel, one Professor Joseph Weiler, Editor in Chief of the European Journal of International Law, will face a Paris criminal tribunal this June for refusing to suppress a review of a book by Karin Calvo-Goller of Israel’s Academic Centre of Law and Business. Calvo-Goller is claiming that the unfavourable review could “cause harm to [her] professional reputation and academic promotion”. Keller refused to pull the review because he did not feel it constituted “egregious unreasonableness” but was part and parcel of normal academic hurly-burly.

This is perhaps the first time that a more general curse of our times - compo culture - has afflicted the academy. As with the continuing legal wrangle here, between the British Chiropractic Association and science journalist Dr Simon Singh, should this case go awry the consequences for free and open discussion of ideas are serious – and not least for academic recruitment. The UK’s draconian libel laws, designed to protect the weak but which now serve to safeguard the strong, combine repressiveness with disproportionate damages. As a result, libel tourists flock here, including every manufacturer of a gimcrack gizmo based on dodgy science, seeking redress each time an academic speaks the truth.

Between the Scylla of an overweening “accountability” industry and the Charybdis of legal proceedings, there remain precious few freedoms for a profession that once drew the admiration of all.